They may have been the first manufactured boy band but The Monkees’ influence runs deep in popular (and not so popular) culture.

It’s fair to say The Monkees were the first manufactured pop band ever. They began in their own TV show which was weird, funny, zany, unconventional and like nothing we had ever seen on telly. The Monkees were good looking, cool, lovable and played catchy pop songs. Everyone, boys and girls, had their own favourite Monkee. What’s not to like? But, like Pinnochio, this manufactured band wanted to be real and this is where the story of the fictional Monkees and the ‘real’ Monkees started to get really interesting.

In the summer of 1965 two young Hollywood brats, Bert Schneider and Bob Rafelson, had the bright idea of putting together a fictional band for a TV sitcom with a difference. Like so many others in the entertainment industry Rafelson, a wannabe film director, had been inspired by The Beatles‘ first film, Dick Lester’s A Hard Day’s Night, and thought the unconventional loose narrative and zany style could be transposed into a series for young people bored with the formulaic nature of most American TV shows. The explosion of pop music and New Wave film in the early 60s had convinced Rafelson and Schneider that this was the future of TV and film and they were eventually proved to be right. Rafelson went on to direct unconventional narrative classics such as Five Easy Pieces, starring unknown actor Jack Nicholson, and the King of Marvin Gardens while Schneider produced left-field classics like Easy Rider, The Last Picture Show and Drive, He Said and both were instrumental in creating a stable of thrusting, talented young directors including Francis Ford Copolla, Martin Scorsese and Henry Jaglom. Unknown to them at the time, they had invented the Hollywood New Wave. And it was all down to The Monkees.

However, the story could have been very different as Rafelson and Schneider had initially wanted John Sebastian and The Lovin’ Spoonful to take the parts of the fictional group. The band were allegedly up for this but their current recording contract stopped them from any further involvement in the project.

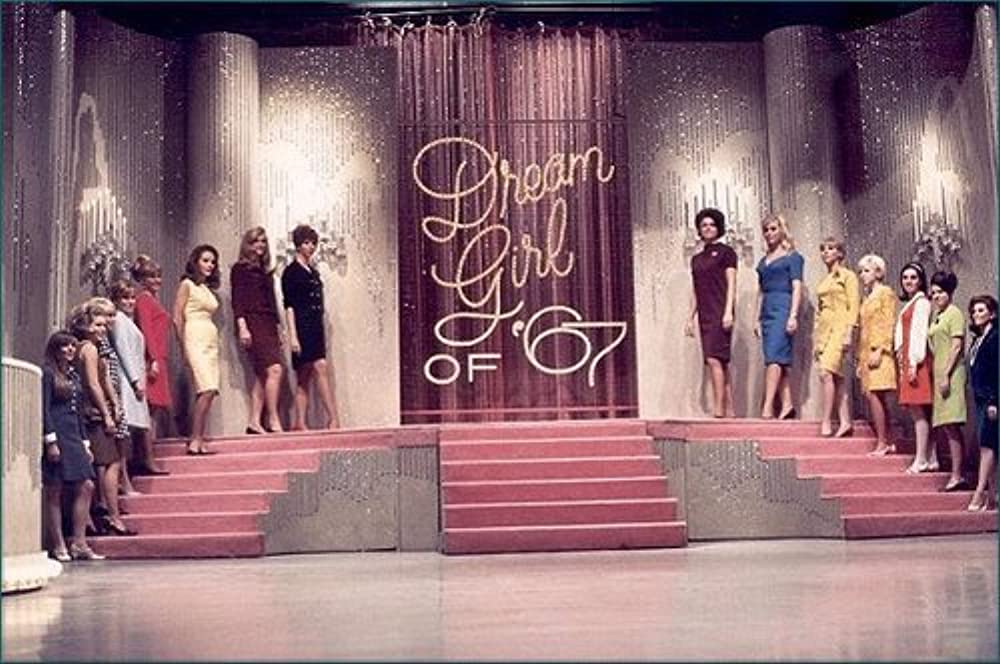

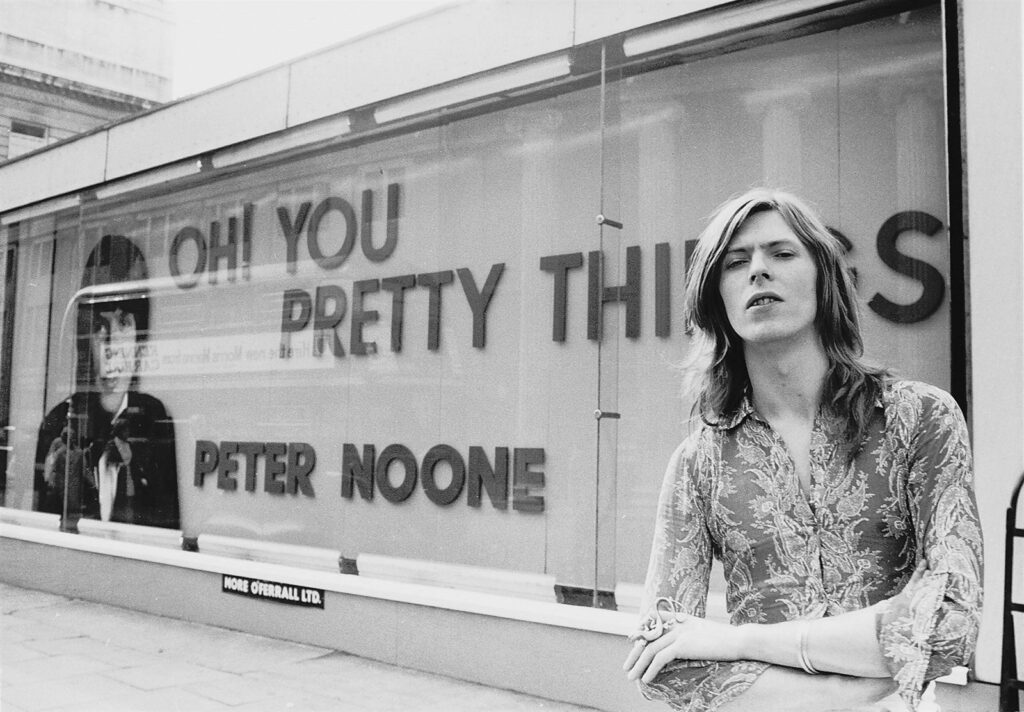

So the story of The Monkees probably began on 9 February 1964 when The Beatles made their sensational debut in front of 73 million TV viewers on American TV on the legendary Ed Sullivan Show. To make the cuddly mop-tops feel at home the producers also included some British acts on the same bill. Apart from the slightly bizarre inclusion of ‘Two-Ton’ Tessie O’ Shea appearing on Broadway at the time also appearing were the cast of the British West End production of Lionel Bart’s Oliver! which had also transferred to Broadway. And playing the Artful Dodger that night was a certain David Jones who watched The Beatles from the wings and decided he wanted to be a pop star too.

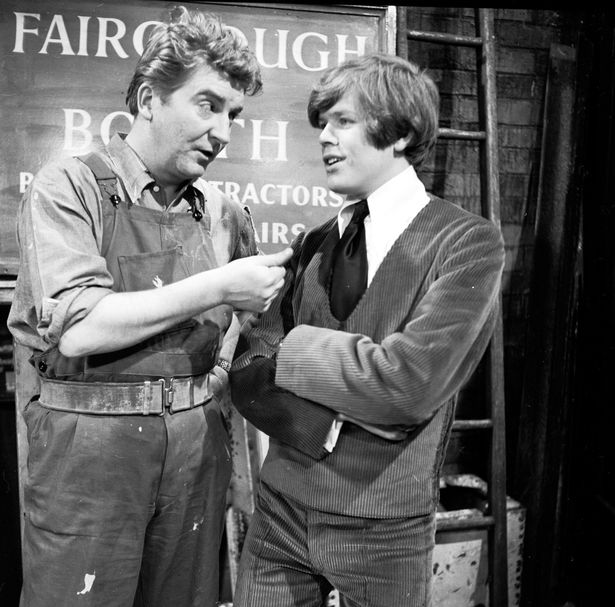

Davy Jones had been a child actor in the UK and appeared as Ena Sharples grandson in a 1961 episode of Coronation Street before deciding his diminutive stature might be more suited to being a jockey. Despite being a success at horse racing he was eventually persuaded to return to acting for the part in Oliver! and after the transfer to Broadway he was nominated for a Tony. During the zenith of Beatlemania when all record, TV and film companies were desperate for something with even a tenuous connection to The Beatles, this got him noticed and he was signed to appear in TV shows for Screen Gems, films for Columbia and to record for Colpix Records. Schneider and Rafelson entered into negotiations with Screen Gems about their groundbreaking idea for a TV show and Jones was offered as it fulfilled Screen Gems and Colpix’s contractual obligations and, most importantly, he looked a bit like a Beatle and he sounded like he came from the centre of the teenage universe of the time, Liverpool! Americans, of course, wouldn’t know the difference between a scouse and a Manc accent. He was a shoo-in as a Monkee but what about the other three?

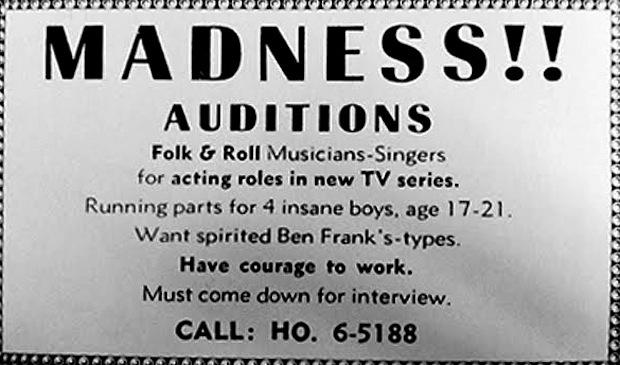

An advert was placed in the September 8-16 editions of Variety and The Hollywood Reporter.

The ad was quirky and left-field enough to appeal to a certain type of young person. The language suggested that this was not going to be a straightforward, formulaic gig. Words like ‘insane‘, ‘spirited‘ and ‘courage‘ made out that this was not going to be for everyone. And ‘Ben Frank’s types‘ was a reference to a well-known Hollywood restaurant that attracted a non-mainstream clientele such as Frank Zappa and Jim Morrison. Someone looking for a role in ‘Days Of Our Lives‘ could forget it.

Given the number of young male wannabes in Hollywood at the time, or, for that matter, any time, the ad attracted only 437 replies. Of the four eventual Monkees, only Mike Nesmith spotted it. Davy Jones was already chosen, Micky Dolenz’s agent referred him to it and it was, of all people, Stephen Stills who alerted Peter Tork to the opportunity. The story goes that both Stills and Tork were playing in the dives of Greenwich Village and knew each other. Stills was auditioned but the producers didn’t feel he was quite right so he recommended Tork.

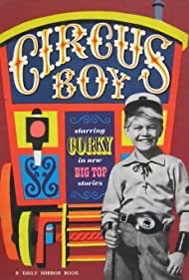

So The Monkees were born. In Jones and Dolenz the production had two experienced actors, Dolenz had starred in the 50s TV series ‘Circus Boy‘ billed as Micky Braddock, and in Nesmith, whose mother had invented Liquid Paper and eventually sold her company to Gillette for the equivalent of $200,000,000 in today’s money, and Tork, two experienced musicians. What could go wrong? Quite a lot as it happened.

The boys all performed a particular role. Davy Jones was the handsome lead singer who looked like he could be a Beatle, Micky Dolenz was the nutty, funny one, Mike Nesmith was the clever, sensible one (although I thought he was a bit dull), and Peter Tork was the daft, not very bright one, although he was the most talented musician and a bit of an intellectual in real life.

The configuration of the band was the first stumbling block. It was decided by the producers that as they were proper musicians Nesmith would be the lead guitarist and Tork the bassist, despite Tork being a more accomplished gutarist. Davy Jones was a competent drummer but it was felt his diminutive stature would lead to him disappearing behind the kit, so Dolenz, who could also play the guitar, was taught some basic beats by multi-instrumentalist Peter Tork and Jones would be lead singer. At least this was the official explanation. My guess is that producers felt that the lead singer should be Davy Jones whose Beatle-like looks and English accent would be more appealing to the teenage target audience who were living through the peak of Beatlemania. But it didn’t matter, they weren’t a real band. They just had to pretend to be real. And this is where the problems really began to emerge.

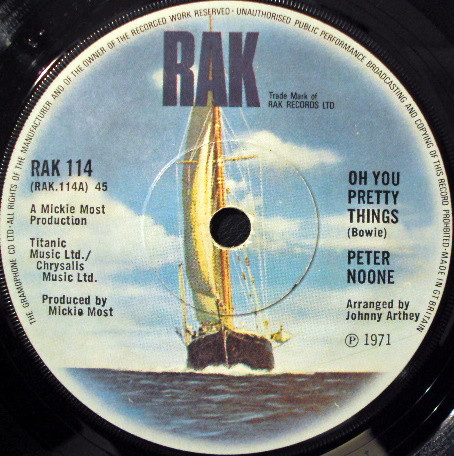

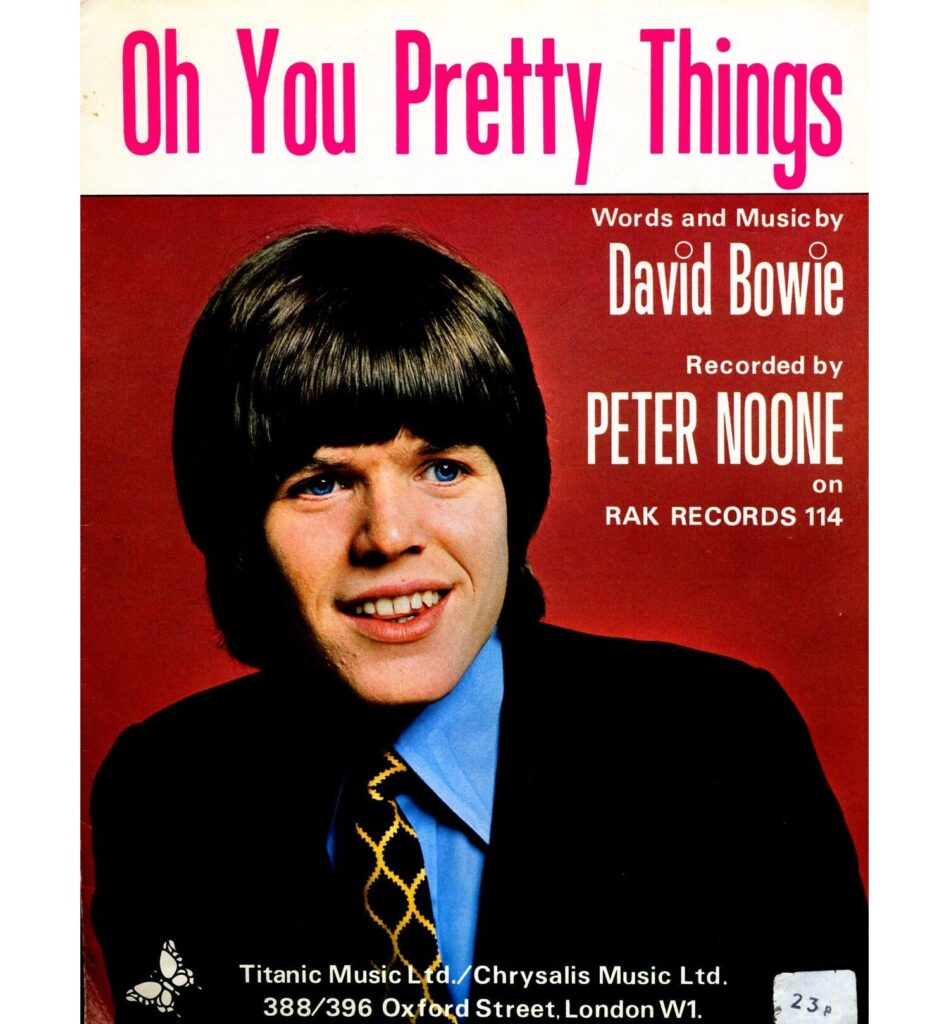

Rafelson and Schneider had brought in mega-music producer Don Kirshner to supervise the group along with up and coming writers Tommy Boyce and Bobby Hart. Boyce and Hart wrote the iconic Monkees’ theme and their first single release Last Train To Clarksville. The single was released a few weeks before The Monkees show was broadcast and went to No. 1 on the Billboard chart. In fact, only Dolenz, Jones and Tork sang on the track and the music was played by The Candy Store Prophets, Boyce and Hart’s band. To say The Monkees were unhappy with this situation was an understatement and bit by bit The Monkees would begin to take control of their music and Kirshner would go. His release of The Monkees‘ second album without the band’s knowledge was a bridge too far. Some of Dolenz and Nesmith’s songs began to appear on their subsequent albums and in the show while many of their singles were written by the creme de la creme of American Brill Building songwriters such as Goffin and King, Neil Diamond and John Stewart.

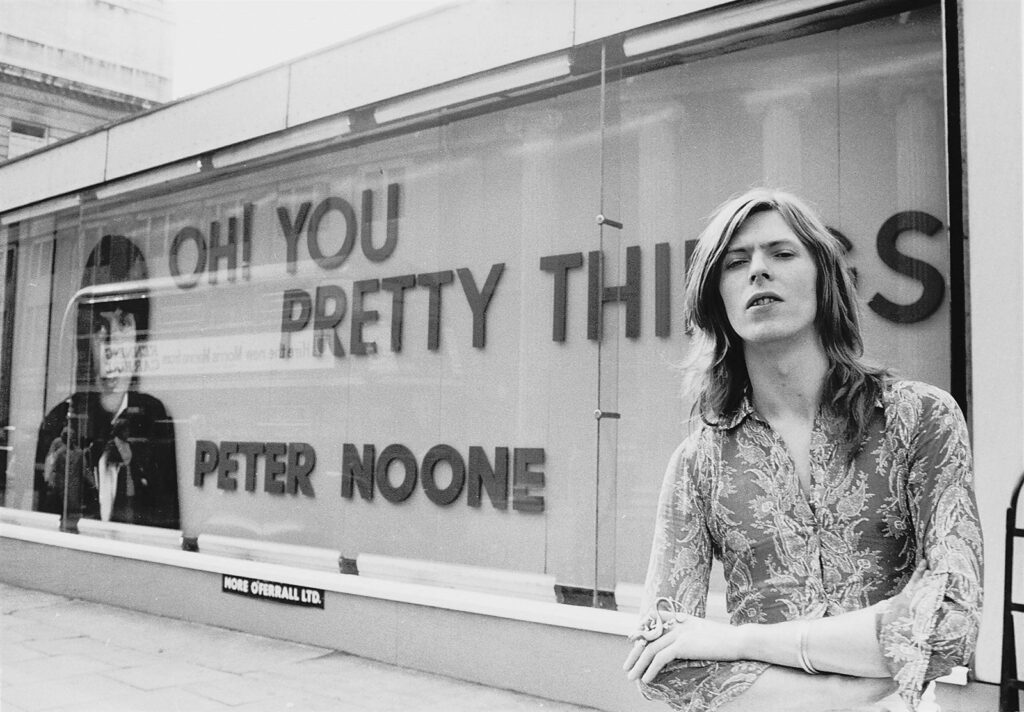

The Monkees‘ next four singles, on which all band members performed, all charted in the top three: I’m A Believer and A Little Bit Of Me, A Little Bit Of You, both written by up and coming songwriter Neil Diamond, Goffin and King’s Pleasant Valley Sunday, and Daydream Believer written by the underrated John Stewart.

The Monkees‘ fourth hit in the UK was an interesting one. Not released in the US, Randy Scouse Git was written by Micky Dolenz and reached No. 2 in the UK Hit Parade. The title was made up of three words few people in the US would recognise. While in the UK Dolenz had watched the controversial for the time sitcom Till Death Us Do Part and heard Alf Garnett refer to his Liverpudlian TV son-in-law by this name. Of course, the buttoned up British record company told the band it was too offensive and they’d have to come up with an alternate title. So the song became known as Alternate Title, just to hammer home the point the real title was more interesting. The performance on The Monkees show featured Liberace smashing a piano with a hammer. If that’s manufactured pop, I’ll be a Monkee’s uncle. A curiosity amongst The Monkees‘ back catalogue.

What Rafelson and Schneider had hit upon was the first TV show in which music videos could be broadcast, all of which led to the band having a smash hit without having to worry about the radio picking the songs up. Whether they were aware of this is unknown but my guess is they were just trying to pull back the boundaries of narrative on TV. Both were aware of the French New Wave, Rafelson had admired Japanese cinema while in the military in the far east and both were very much part of the burgeoning US counter-culture. Hence the show not only threw out the TV rule books it also ripped them up and cast the pieces to the four winds.

Directors and writers were given carte blanche to create the most anarchic, zany and unconventional half hour of the TV week. They did this by systematically raiding the French New Wave playbook and the series included, for example:

- Unusual camera angles and movement

- Jump cuts

- Flashbacks

- Weird visual effects

- Cartoonish sound effects

- Hand held cameras

- An absurdist sense of humour

- A perfunctory observation of the narrative

- A feeling of improvisation

- Outlandish characters

- Songs featured as pop videos

- Smashing of the fourth wall with the actors talking directly to camera

In other words, nothing was off the table. Many references were made to other hugely popular shows on US TV at the time including that other 60s phenomenon Batman (See Batman: A 60s Sitcom Phenomenon).

When some of the shows had under run Bob Rafelson would gather the boys together and ask them about issues concerning young people at the time and slot their responses into the final few minutes of the show. Teenage riots in LA, long hair and generally how older people treated ‘da kids’ were all analysed for three minutes before the closing credits rolled.

For the second series the band’s increasing influence was in even more evidence. A self-penned Monkees’ song, Peter Tork’s For Pete’s Sake, became the song which accompanied the show’s closing credits. They were even successful in persuading the producers to drop the laughter track from the latter part of series 2.

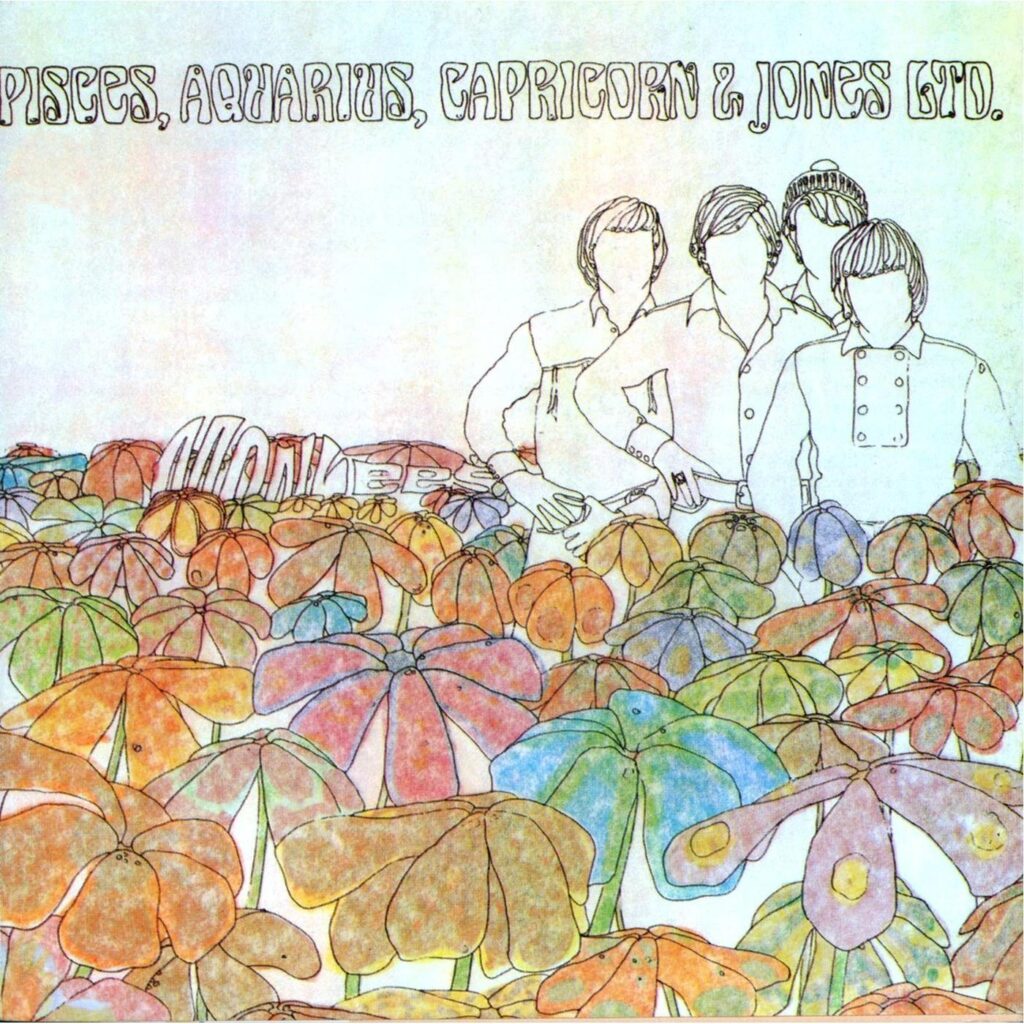

By the time they had released their fourth album in November 1967, Pisces, Aquarius, Capricorn and Jones Ltd, they were not only playing and writing some of the songs, they were also seen as being prestigious and ‘cool’ enough to attract an array of top class session musicians and guests to contribute. Glen Campbell, The Byrds, failed Monkee Stephen Stills, Little Feat’s Lowell George, and even Neil Young all weighed in on the album. It became their last No. 1 album with most of the songs being featured in the show and Pleasant Valley Sunday being the spin-off top three hit from the album. The cover is a ‘flower-power’ representation of the band with their faces obscured. An attempt to move away from the teen pretty boy image they had perhaps?

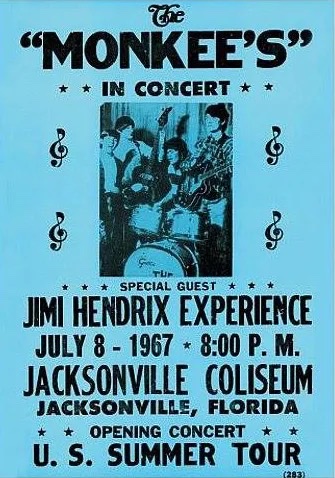

Their live tours were also hugely successful and their July ’67 gigs were opened by a certain Jimi Hendrix although he didn’t go down well with the teenage Monkees’ fans and left the tour early. However, it was an indication of how their teeny-bop image was beginning to change.

In February 1968 NBC announced it would not be renewing The Monkees‘ contracts for a third season. A few years later Davy Jones was said that The Monkees never broke up, they just didn’t have their contracts renewed. This was true in a sense with regards to the TV show but the band did stay together for a few years until the end of the 60s. Surveys showed that since 1967 more young people were listening to The Monkees music than were watching the TV show. So maybe NBC’s decision was based on this finding. It also showed the band had transcended their show and really were a real band rather than their fictional version. It was not the end for NBC and The Monkees though, and the plan was to film a series TV specials, although only one was ever made, 33 1/3 Revolutions Per Monkee.

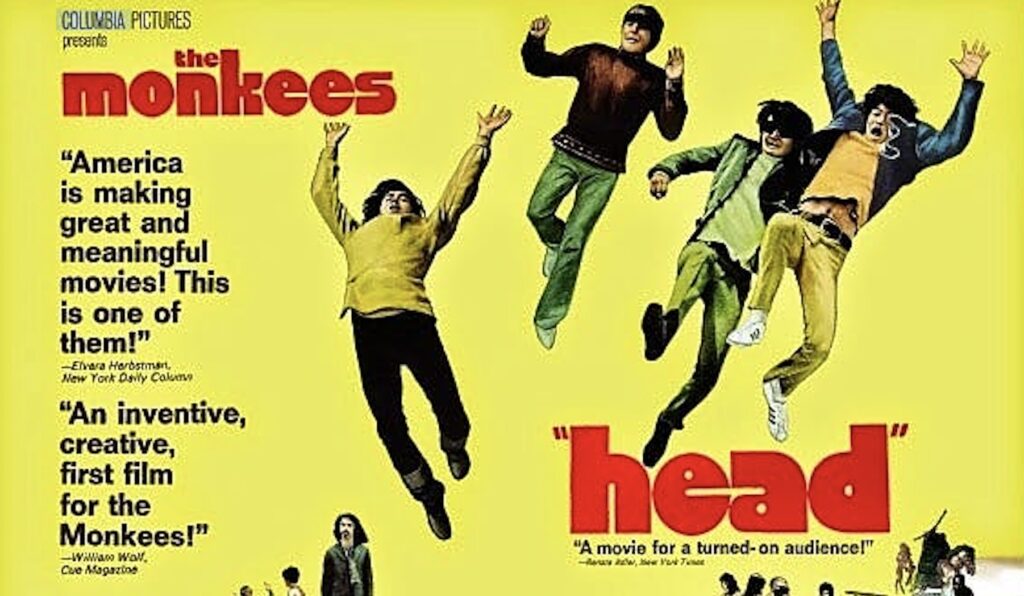

At almost the same time their TV show was cancelled the band embarked upon their most un-Monkeeish project ever. Conceived by Rafelson and a young, almost unknown Jack Nicholson, Head was to be a characteristically late 60s psychedelic film which, in Nesmith’s view, was designed to ‘kill’ The Monkees. Some felt that The Monkees, having achieved all they set out to achieve, were holding back Rafelson and Schneider from the projects they really wanted to move on to, e.g. Easy Rider, Five Easy Pieces etc, and they could thank The Pre-Fab Four for providing the finance to do pretty much, anything they wanted to. In many ways The Monkees changed the course of American cinema. It’s maybe fair to say Head did kill off the fictional Monkees and leave the ‘real’ Monkees to do what they really wanted but, sadly, their time at the zenith of world pop was almost at an end.

The psychadelic, scattergun approach to narrative and image in Head alienated the band’s teenage audience, while the older, more ‘serious’ music fans who didn’t like The Monkees anyway, were not persuaded by this. The film was, unsurprisingly, a critical and financial flop. However, critics over the past few years looking back at Head have been more generous seeing it as a product of its time and ‘well worth seeing.’ It has been broadcast rarely in the UK although I do remember watching it on Channel 4 in 1986 and really loving it. But I’ve always been attracted by the weird.

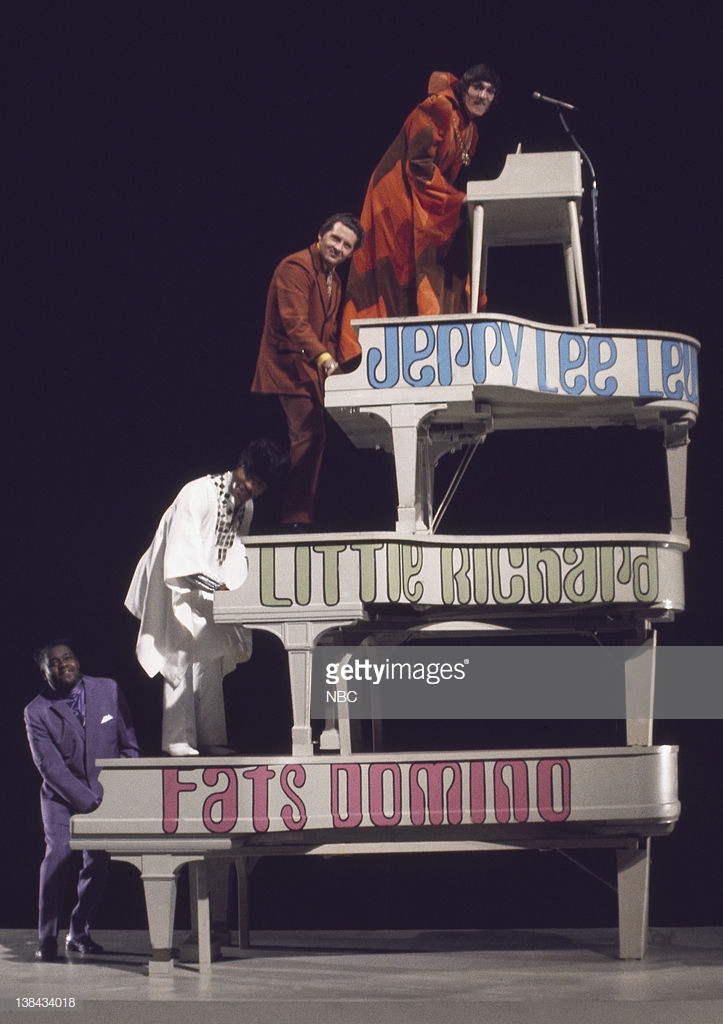

The Monkees final act together, however, was suitably strange after the completion of Head. 33 1/3 Revolutions Per Monkee was broadcast in the US on April 14 1969 and was the first of what was originally planned to be a series of Monkee TV specials but turned out to be the only one. It was also the last time The Monkees played as a quartet until 1986. Mike Nesmith described 33 1/3 as ‘..the TV version of Head,’ and it certainly was very different to the TV shows The Monkees were known and loved for. In what seemed like another attempt by the band for pop credibility they were joined by Little Richard, Fats Domino, Jerry Lee Lewis and, maybe surprisingly, Julie Driscoll, Brian Auger and The Trinity, who were one of the acts that represented the psychedelic scene of the 60s.

It told the story of the band being taken through the different stages of evolution by Driscoll and Auger and along the was they perform various songs individually and as a group. Driscoll, for example, performs a version of I’m A Believer with Dolenz while the whole band perform doo-wop hits with all the guest stars.

After 33 1/3 the Monkees carried on as a trio and still had a huge fan base to fall back on, but as Dolenz observed in 1969, ‘..it was like kicking a dead horse. The phenomenon had peaked.’

During their final year together they appeared on a range of prime time variety shows such as The Glen Campbell Goodtime Hour, The Johnny Cash Show, Hollywood Squares (Celebrity Squares to us) and a few appearances on the happening show of the time, Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In. They even appeared in an ad for Kool-Aid with Bugs Bunny.

But The Monkees‘ still exhausting schedule became all too much for Peter Tork however, and he was the first to officially leave the band at the end of 1969. It cost him a huge amount of money to buy out the four remaining years of his contract and he never really recovered financially from it for the rest of his life. During the mid-70s he even taught at Californian school for a few years.

The Monkees continued to play live intermittently for the next 40 years in various line-ups, their songs always remaining popular and their fan base staying strong. Sadly Jones died in 2012, Tork in 2019 and Nesmith in 2022.

They may have been hated by ‘serious’ music fans at the time but their legacy is huge. Everyone still knows every Monkees’ classic hit, their TV show set the template for other unconventional TV shows and an anarchic type of comedy right up to the present, without them we would not have had the New Hollywood of Coppola, Scorsese, Rafelson, Bogdanovich or even Spielberg and crucially they showed how it was possible to break free of the strictures of TV and record companies who wanted a particular look or image. And what a great pop back catalogue they left.

The Monkees were so much more than just a manufactured pop band.