Savaged by the critics on release, Kubrick’s masterpiece The Shining is now the Ulysses of film analysis

More has probably been written about Kubrick’s 1980 classic The Shining than any other of his canon, even 2001: A Space Odyssey. But what is it that compels sad people like myself to be constantly analysing every scene, every character, every iconographic element, every shot, even things that are not necessarily there?

But isn’t this why so many films prevail and maintain their interest with the viewing public and why so many films become classics rather than those that sweep over you and you’ve forgotten everything about before you’ve left the cinema?

It’s a criminally overused word and I’d avoid using it if I could but The Shining encapsulates everything about the adjective ‘iconic’. For me, it’s one of the few films that is not only better than it’s source material but actually transcends its genre. It irritates me hugely when I hear people refer to it as a horror film. It’s so much more than that. So much so that I won’t even try to describe it generically. On its release so many critics dismissed it for not having ‘enough shocks‘, for being ‘too slow or plodding‘ in its narrative, characters who were ‘hard to connect with‘. It was more than 10 years before critics began to re-evaluate it and see it as a film that broke generic, narrative and technical boundaries and it’s why viewers are still discussing it today.

Stanley Kubrick only made 12 films in 45 years. Half of this number were made in his first 10 years as a major studio director between 1955 and 1964. But his output not only became increasingly complex in style and narrative but covered most genres including science fiction, historical drama, comedy, war, dystopian fantasy and, ok, horror (but in its widest possible context!). His blockbuster SF film which trumpeted the fact ‘genius at work‘, 2001: A Space Odyssey was like nothing ever seen before in cinema. Over 50 years after its release it still seems way ahead of its time. The success of 2001 meant Kubrick could pick and choose what his next project was going to be and, true to form, he surprised the film world by choosing a fairly obscure dystopian fantasy novel by prolific British writer and academic Anthony Burgess, A Clockwork Orange (much more on this below). The furore this film caused, particularly in Kubrick’s adopted home in the UK caused him to withdraw it within a year of its release. He went on to make the uncontroversial historical drama Barry Lyndon, again from a lesser known Thackeray novel which, although performing reasonably well financially, it was, at the time, seen as a critical failure. Like so many of Kubrick’s films, Barry Lyndon has been re-appraised in recent years and seen as much more of a success than it was when released.

After the critical maulings he received for A Clockwork Orange and Barry Lyndon, Kubrick decided on a different approach to his next project. He was going to make a film that would have widespread appeal due to its subject matter but would bear heavily the unique Kubrick stylistic imprint. And after reading many, many horror stories (some for only the first couple of pages) he landed upon a recent Stephen King novel entitled The Shining. Here he could see possibilities but that meant jettisoning much of King’s original story and retaining, pretty much, only the conceit and general framework of the source material. This, of course, did not please Stephen King although, over the years, he seems to have made his peace slightly with Kubrick’s version. And so he should as Kubrick removed many of the silly fantastical elements such as topiary animals which come to life and much of the run-of-the-mill hotel backstory and created an atmosphere and narrative that still fascinates.

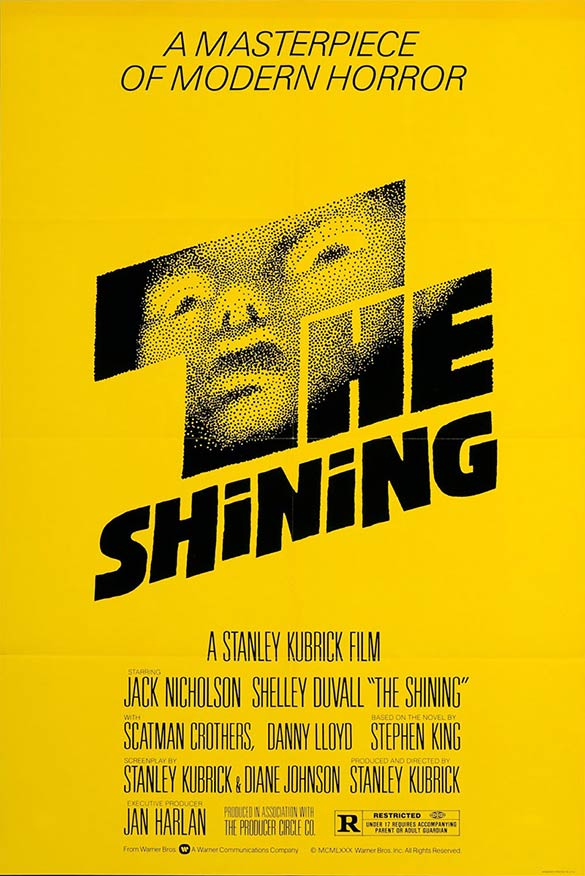

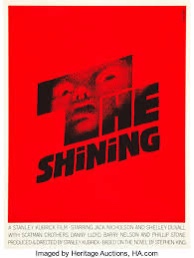

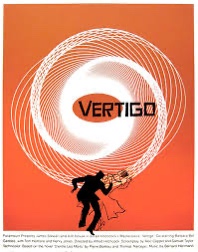

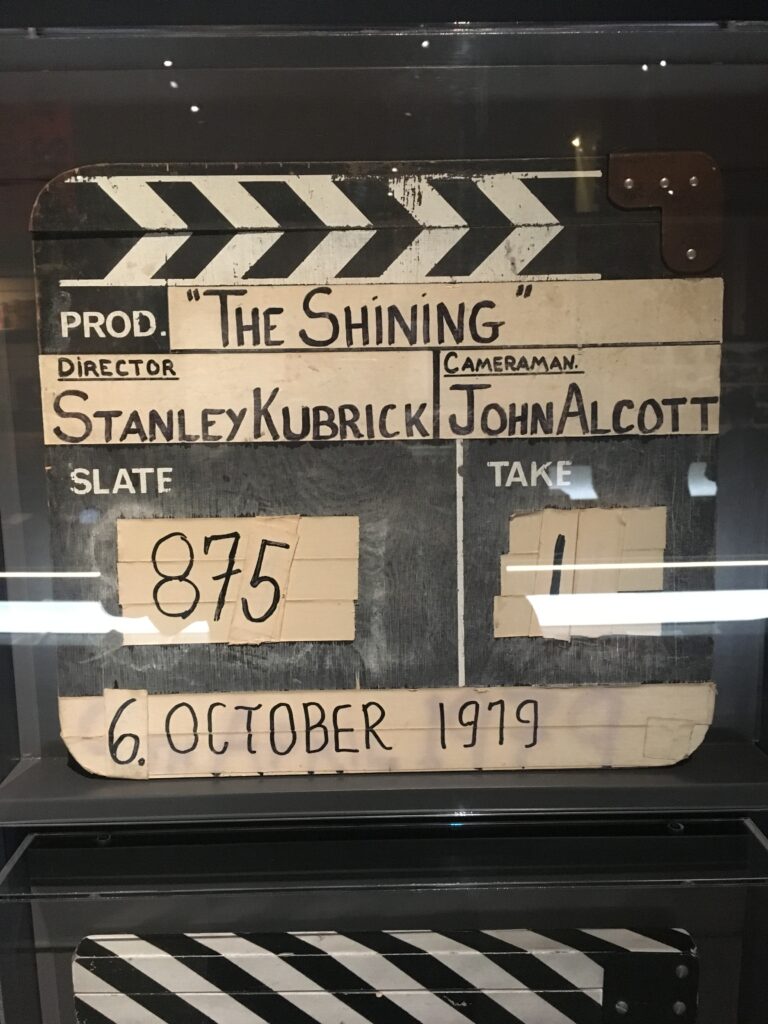

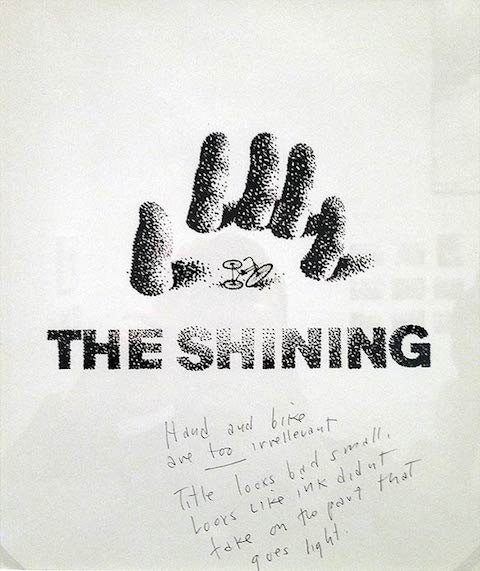

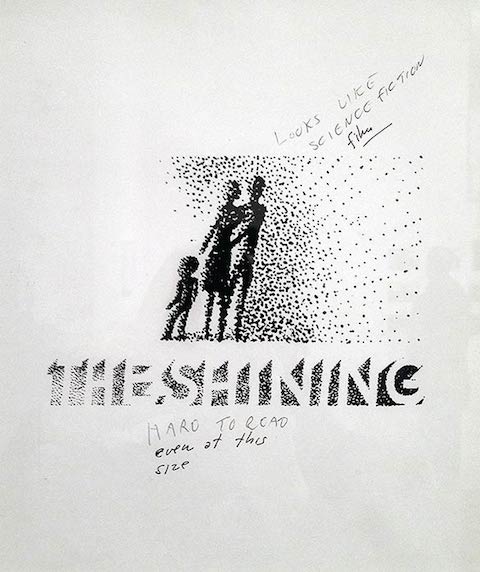

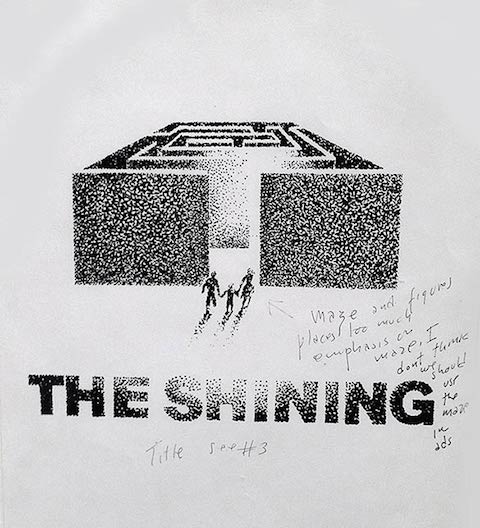

To begin with the poster for the film is as enigmatic as the film itself. Kubrick was big enough in the film world at the time to go for the best and it was to the legendary Saul Bass he approached to come up with something suitably cryptic. Bass was responsible for classic poster and opening credit sequences for some of the greatest films ever made. In fact, often Bass’s work is remembered when the film may not be. He’s even credited with directing one of the most famous and most brilliant scenes in the history of cinema, the shower scene in Hitchcock’s Psycho.

And Bass didn’t disappoint in the esoteric stakes coming up with an image that didn’t even appear in the film. Bass’s original design was red and featured a pointillistic, cartoonish doll-like character but typically Kubrick liked the image but opted for a yellow rather than red poster. Recently I attended the Kubrick exhibition at The Design Centre in London. There they displayed a number of other designs Bass had come up with, many of which, to me, were considerably more effective than the poster chosen. But there’s no point in attempting to fathom why Kubrick made the decisions he did. You just have to assume he’s usually right.

I don’t intend in this blog article to even summarise the story of The Shining as, in the unlikely event of anyone reading this article, most people will have seen the film anyway or at least know what happens in it. My purpose is to highlight some of the elements which make The Shining a film that so people return to again and again and constantly reinterpret. So my approach, as usual, will be scattergun, rambling and sometimes abstruse but this is what The Shining brings out in people like me. And I couldn’t be happier about that.

The film begins in suitably Kubrickian expansive way with aerial shots of the Torrance’s yellow beetle car moving beetle-like across a vast Coloradan landscape. Kubrick used electronic composer Wendy Carlos again to create the dark, foreboding, brooding soundtrack which accompanies the main characters journey towards their winter caretaking stint at the soon-to-be desolate Overlook Hotel in the Colorado mountains. Carlos had created the futuristic soundscapes for Kubrick’s previous film A Clockwork Orange and The Shining would be her last collaboration with Kubrick as, according to her, too many compositions to accompany scenes in the film did not make it into the final cut. Anyone watching this film for the first time would be left in no doubt that these tiny characters were heading towards adversity given the tone and atmosphere built up by the musical opening.

The central character, Jack Torrance is played by Jack Nicholson who was Kubrick’s first choice for the role. Other actors to be considered included Robert De Niro, who it was possible to envisage as Torrance, Robin Williams, who it wasn’t, and Harrison Ford, who would have been more in keeping with Stephen King’s ideas for the part. Rather than Nicholson’s manic and menacing turn almost from scene 1, King wanted to see a decent character gradually deteriorate psychologically becoming a threat to his family through months of cabin fever in the Overlook Hotel and due to other types of supernatural influence. Nicholson’s performance was ridiculed as being overblown and hammy by many critics at the time but and one can’ t help but think that the meticulous Kubrick liked the idea of Nicholson’s, allegedly, coke-fuelled mania which just added to Torrance’s psychological collapse and descent into madness.

Jack’s first major appearance where he is interviewed for the job of out-of-season caretaker at the Overlook Hotel immediately sets the scene for the rest of the film. He’s informed of a brutal murder which took place around 10 years before when the caretaker, at the time, Charles/Delbert Grady, went mad and killed his wife and two young girls with an axe. From then on Jack’s mental deterioration and gradual homicidal path is brilliantly represented through a series of masterly images and set pieces, leading to a ground-breaking steadi-cam inspired denouement in the hotel’s freezing maze.

The interview scene is intercut with scenes of Danny talking to a character he refers to as ‘Tony’ who is ‘inside his mouth’ who ‘tells him things’. Through Tony, Danny can see into the future and possesses abilities ordinary people don’t. Tony tells Danny something so terrifying Danny faints in utter shock and we are made aware that this has to do with the place they are going to be spending the winter the Overlook Hotel. When they arrive there Danny immediately strikes up a friendship with the hotel’s cook, Halloran, who has the same abilities and calls it ‘shining.’ Halloran is able to see Danny has these abilities but also makes him aware of what might happen when he is in the hotel alone and warns him off entering room 237. Soon Danny is seeing disturbing images from the hotel’s past which link to what Jack was told during his interview.

Much of the debate about the film surrounds the question of whether the hotel is actually haunted by the ghosts of its bloody past or is it all happening in Jack and even Wendy and Danny’s heads. This is where Kubrick diverges significantly with King. In Kubrick’s Overlook events are open to interpretation, nothing is ever quite what it seems and often metaphorical.

One of the enduring and memorable images from the film is of the elevator doors in the main reception opening and a torrent of blood emerging from them. This is a nightmare Danny experiences on more than one occasion, a nightmare that foreshadows the terrible events awaiting him at the Overlook Hotel.

Another criticism of the film, according to critic Roger Ebert, is that it lacks a ‘reliable’ observer. Jack is clearly unreliable from almost the moment he enters the hotel, Wendy is too sensitive and almost afraid of Jack to be aware of everything happening around her and there is so much going on in Danny’s head that it’s difficult to know just what exactly is really happening at any point in the film. This, I believe, is exactly what Kubrick wanted, if the characters are confused and bewildered then so will the audience.

All three characters see the ‘ghosts’ of the hotel at different times. Danny sees them from almost the moment he enters the hotel and this is due to his supernatural abilities. But Jack’s spectral encounters take longer to happen and are more problematic. Does he really see ghosts or is it his deteriorating psyche that is responsible for these illusions or even his alcoholism? Kubrick, of course, deliberately creates these enigmatic confrontations.

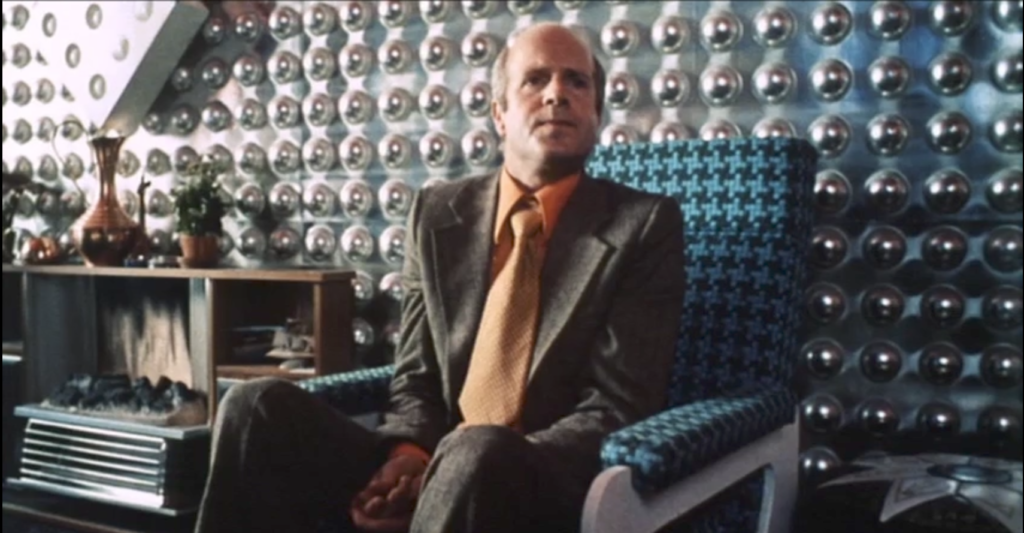

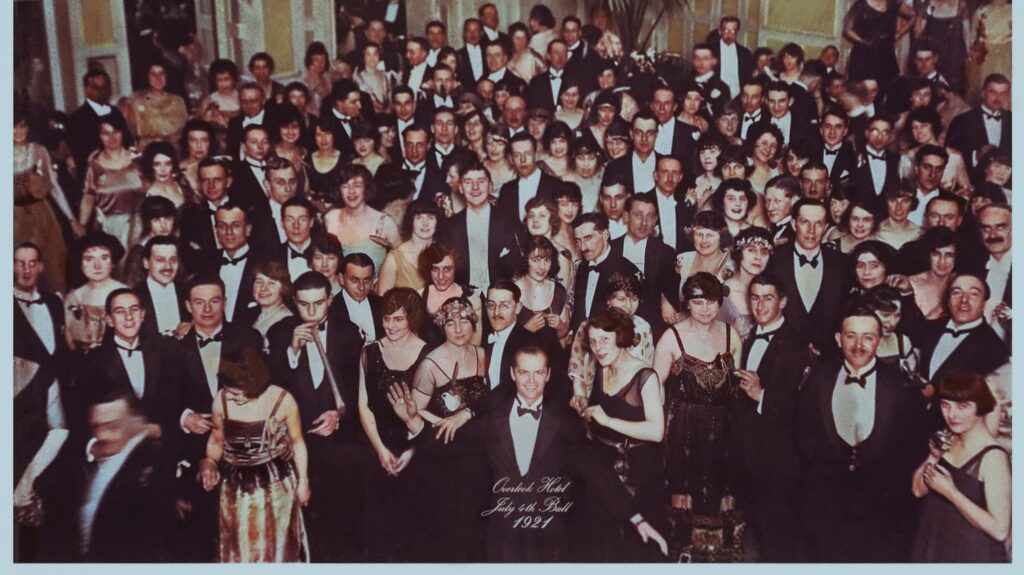

Jack’s first meeting is with barman Lloyd after being accused by Wendy of attacking Danny. Here we find that Jack may have a problem with alcohol after he relates the story of when he injured Danny when he was still very young. Lloyd plies Jack with whisky, ‘Your money’s no good here Mr Torrance.’ But is this merely Jack losing his grip on reality with his desperation for a drink fermenting his delusions. Is he really drinking alcohol or just imagining it? Later in the film Jack walks into the ballroom again and this time it’s populated by the ghosts of the guests of the hotel from many years ago. As well as encountering Lloyd again he literally bumps into Delbert Grady, the former caretaker who killed his family some years previously. A chilling conversation takes place in the blood-red toilet as Grady cleans up the drink he spilt on Jack. It is here that we as viewers begin to almost accept that Jack is in conversation with a murderous ghost as Grady warns him of Halloran coming to help Danny and Wendy. If Grady was a figment of Jack’s feverish imagination how would Jack have known this? Grady advises Jack euphemistically that maybe Danny and Wendy need ‘correcting‘. We , as viewers at this point, know exactly what Grady is suggesting.

These pivotal ‘ghostly’ scenes where Jack supposedly meets both Delbert Grady and Lloyd the barman feature two stalwarts of Kubrick films, Philip Stone and Joe Turkel. Both actors appeared in three Kubrick films, more than any other actor. Stone also appeared in A Clockwork Orange and Barry Lyndon, Turkel in The Killing and Paths of Glory. Both play parts of chilling low-key menace.

A second similar question arises when Jack is locked in the food store by Wendy. He hears Grady outside once again encouraging him to bring Danny and Wendy into line. And eventually the door is opened for him. If not a ghost, who lets Jack out? A few theories have been suggested as to how Jack escapes from the store room. For me the most plausible is that Danny let him out. Maybe Danny knew that this was the only way he was going to stop Jack murdering his mother and him and leading him into the maze was the most effective way. So why didn’t Kubrick let us see Danny do this? For the same reason so many other events were cloaked in mystery. Of course the director wants to keep us guessing, hence the lack of a reliable narrator which is just too predictable for Kubrick. He wants us to be as bemused, bewildered and beguiled as the characters. So if that’s the smoke, what about the mirrors? You may well ask.

As Jack prowls around the corridors and rooms of the Overlook, each time he appears to encounter some sort of apparition, mirrors are very close by. In Room 237, in the toilet when he encounters Grady, at the back of the bar when he encounters Lloyd the barman and even on the shiny metallic door when he hears Grady outside the storeroom. So does this mean that these ghosts are real or are they just transpositions or reflections of his own crumbling sanity? Is the evil he is apparently confronting just the mirror image of his own psychological deterioration? In the novel Jack finds a scrapbook which includes news clippings and photographs of things that happened at the Overlook since its opening in 1910, he already knew about Grady and maybe Lloyd the barman was a former employee he read about. In the film we see, at one point, the scrapbook sitting on Jack’s work table but is never referred to. It seems as if Kubrick, once again, decided that this was too much of an explanation or backstory for the events that followed and that he’d prefer viewers to be left rather more in the dark.

And let’s not forget about Wendy. Despite being oblivious, seemingly, to some of the things that are happening before her very eyes, when the shit hits the fan and she is frantically looking for Danny through the dimly lit back corridors of the Overlook, she almost literally bumps into some of the ghosts of the hotel past. The elderly man with the wound in his head, the man in the bear suit performing something beastly on another tuxedoed guest suddenly appear to her. Why?

In the US version of the film she runs into the ballroom to be met with previous guests, maybe the ones that were partying when Jack stumbled into Grady, but this time they are all skeletons. Strangely, Kubrick cut this scene from the European version of the film. Once again, did he feel a European audience didn’t need to be hit over the head metaphorically with images showing the ghosts of the hotel revealing themselves to Wendy? The skeleton scene, for me, is a step back into Carry On Screaming territory and detracts from the brilliantly enigmatic aspects of The Shining.

But the question still remains. Why did it take so long for Wendy to see these apparitions? At the start of the film Halloran suggested to Danny that ‘shining’ might run in the family. He said that his grandmother and he used to have conversations without even opening their mouths as they both had the shining. So where did Danny get it? Danny clearly tries to suppress his abilities. He’s almost embarrassed to admit it to Halloran and maybe Wendy has suppressed this talent until she became so stressed that her shining began to manifest itself and she started to see the ghosts of the hotel through her unfiltered perception. Or maybe Jack also has the shining, hence his ability to encounter the characters from the hotel’s past. It might also explain why he knew about Halloran’s return.

The man in the bear suit is puzzling. At first I thought it was a reference to an episode from King’s novel that happened many years before the Torrances arrived at the Overlook. A gangster who stayed there used to humiliate one of his hangers-on by making him dress up and bark like a dog with tragic consequences. However, the man, if it is a man, is wearing what looks like a bear suit. A perfectionist like Kubrick would not substitute a dog suit for a bear suit for no reason. However, Rob Ager at www.collativelearning.com makes a very compelling case for this being part of an elaborate series of clues planted by Kubrick to suggest that Jack had been sexually abusing Danny. Now this might seem a bit of a stretch but it’s worth checking out what this analysis by Rob Ager has come up with. Certainly food for thought.

Another aspect of the film which is far superior to the novel is the ending. In the novel one of Jack’s main roles as caretaker is to look after the antiquated heating system which, after his breakdown, is neglected leading to Danny and Wendy escaping from the hotel with Halloran’s help just as the boiler blows up killing Jack who was still in there. The film version ending features one of the great edits in cinematic history cutting from a long scene with jack bellowing like a wounded animal to a static daylight image of him frozen to death. Sadly, for me, the final slow zoom into the photograph on the wall of the Overlook reception, finally focusing on Jack’s doppelgänger in the July 4th 1921 ball, suggesting Jack has been there in a previous life (You have always been the caretaker…) almost ruins the ending completely. But not quite. It’s as if Kubrick felt he had to throw the audience some crumbs of explanation but he needn’t have bothered, although it probably placated some critics looking for ‘closure’ of some kind.

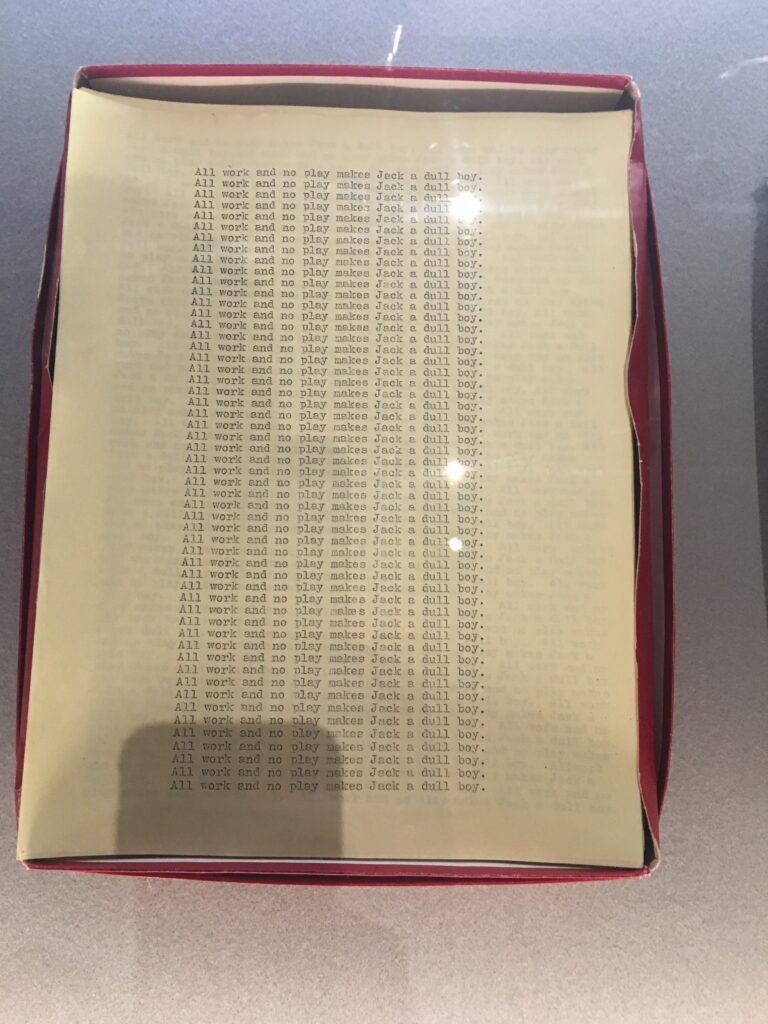

The film has been responsible for a number of interesting contributions to popular cultural. The phrase ‘All Work And No Play Makes Jack A Dull Boy‘ has become synonymous with the film. Jack has been hard at work on his new novel for weeks and even becomes aggressive with Wendy when she interrupts him one day. Jack then disappears from his desk and Wendy looks at the reams of typewritten sheets that he has compiled. To her horror very sheet has this same phrase written in different formations. It is at this point that she realises, although one suspects she always knew, that something has gone seriously wrong with Jack’s mind. Interestingly, other country’s versions used a different idiom to the English version. In Germany it was, rather mundanely, ‘Never Put Off Till Tomorrow What Can Be Done Today.’ Much more poetic was the Italian version: ‘The Morning Has Gold In Its Mouth.’ The French version was slightly more enigmatic: ‘One ‘Here You Go’ is worth two ‘You’ll Have Its’. Hmmm.

The scene in The Shining that everyone remembers is when Jack crashes through the bathroom door with an axe and announces ‘Heeeerrre’s Johnny!’ where a terrified Wendy cowers. When the film was released in the UK in 1979 few people would have recognised that phrase although everyone in the US would have. America’s biggest chat show was The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson with an audience of millions. This programme was not broadcast in the UK at the time although it was for a short time in the 1980s. Johnny Carson would be introduced each night by his sidekick Ed McMahon with a ‘Heeeerrrre’s Johnny! It was as familiar to American audiences as ‘Ooh Betty!’ was to British audiences in the 70s. Although if Jack had used that one instead it might have had a slightly different effect. Two (quite) interesting facts about this iconic scene. Firstly, Nicholson improvised the line at the time and amazingly for perfectionist Kubrick, he decided to leave it in, and secondly as Jack Nicholson was a trained volunteer fireman the door he chopped down was a real one and, once again, given Kubrick’s meticulousness, a great many doors were harmed in the making of this film.

For a film that was described by one critic as ‘A crashing disappointment..’ at the time is now one of the most analysed films in cinema history, Jonathan Romney of The Guardian was closer to the truth when he called The Shining, ‘..a palace of paradox.‘ For a film that was nominated for more Razzies than any other Kubrick title and nominated for no Oscars (the only Kubrick film not to be) it continues to fascinate and puzzle 50 years since its release. This article has only scratched at the surface of this Joycean maze and there are so many more elements that could have been explored but to paraphrase the Italian idiom changed in the film, The Shining has, and always will, have gold in its mouth.

Kubrick’s smoke and mirrors continue to confound.