Fifty years on, The Magic Christian is still relevant so should it be recognised as the flawed masterpiece it really is? Yes!

The Magic Christian was released right at the end of the 60s in December 1969. It starred Peter Sellers, who had become a major Hollywood player around this time, and Ringo Starr who was still dealing with the demise of The Beatles only months previously. It hit the cinemas with hardly a fanfare and disappeared almost as quickly under a deluge of poor reviews. In August 2005 Paul Merton chose the film as part of his ‘Perfect Night In‘ for BBC 2. Previously this film had scarcely seen the light of day since its release and it was really only then that the film could be viewed as one which not only epitomised many of the tropes and attitudes of sixties’ writers and film makers, but also brought together some of the best acting and production talent available in the UK at the time. It was also a fascinating insight into the, often unlikely, motivation of its stars and the type of country it reflected at a time of profound cultural and social change.

The film was based on a novel of the same by American writer Terry Southern whose previous films as writer included Kubrick’s Dr Strangelove and Lolita as well as Easy Rider and Barbarella. Films as sixties as they come. Ringo had appeared in the sex comedy Candy released the previous year and clearly, as probably the best actor out of all The Beatles, which is maybe not saying much, he was intent on a film career post-Beatles. Southern’s novels were certainly ‘counterculture’, satirical, over the top for many, but with extremely serious themes, and The Magic Christian was very much of this genre. It told the story of Guy Grand, played by Sellers, a hugely rich business tycoon who adopts down-and-out Starr seemingly on a whim and, between them, set off on a picaresque journey using Grand’s money to play elaborate hoaxes on the human race, although it’s mainly the establishment and upper class figures who suffer most, who, according to Grand, ‘all have their price.’ The film builds up to a weird climatic sequence aboard a bogus cruise liner named ‘The Magic Christian‘ where the wealthy conceited passengers are made to think the ship is sinking amongst chaos which includes escaped gorillas, a vampire, a dipsomaniac captain and supposed hijackers.

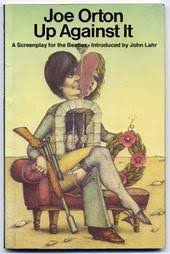

I would even argue that this could have been the fourth Beatles’ film. That, of course, was originally meant to be Up Against It with a screenplay written by Joe Orton in 1967. On the day Orton was supposed to meet director Dick Lester to discuss making the film, the film company’s chauffeur found Orton and his partner Kenneth Halliwelll dead in their Islington flat, Halliwell having murdered Orton and then killed himself. But with Ringo in the cast, music by Paul McCartney, a shot of John and Yoko lookalikes embarking on The Magic Christian and Apple producer Denis O’Dell on board, this was as close to a Beatles’ film as we were ever going to get. Even the anarchic unconventional narrative and arch nature of the film had a Magical Mystery Tour and Help vibe to it.

The soundtrack was by Paul McCartney and first Apple signing Badfinger, who had three top ten hits shortly after the film’s release. Their biggest hit was the film’s opening track, the excellent McCartney penned ‘Come And Get It‘ which chimed with the film’s ‘anything for money’ theme. Other tracks were written by the band who released an album entitled ‘Music From The Magic Christian.’ In years to come two members of Badfinger, Pete Ham and Tom Evans, would commit suicide due to, what they believed, was bad management which stifled their career. In 1970 Harry Nillson had a huge worldwide hit with the Badfinger song, Without You, which the band made little from, and in 1994 Mariah Carey screeched her way to success with the same song. It would be 2013 before Badfinger’s financial affairs were sorted out in court. Far too late for Ham and Evans.

Another interesting Beatles musical note from the film was when the duped passengers piled out of The Magic Christian with the sudden realisation they were still in London, the final crashing piano note to The Beatles‘ classic ‘A Day In The Life‘ is heard.

The anti-establishment spirit and cynicism of the film made it an unlikely vehicle for Sellers who was a hot property in Hollywood and he could have pretty much chosen any project he wanted after impressing in films like Dr Strangelove, The Pink Panther and What’s New Pussycat. The Magic Christian was, therefore, a seemingly strange choice. However, this was a film Sellers desperately wanted to make and in an interview a few years later, director Joe Mcgrath revealed that this was very much Sellers’ project. ‘He found the money. He really believed in the film.’ Up to this point Sellers had given no indication that he was at all anti-establishment or countercultural. In fact, given his ‘friendship’ with Princess Margaret, who attended the premiere, and his well known love of money, it seemed ‘the establishment’ was exactly what he wanted to be part of. So what motivated Sellers to make a film which purported to show the greed and immorality of the human race?

A huge clue was provided in an almost forgotten documentary of the time. During the production of the film a separate documentary was made entitled ‘Will The Real Peter Sellers Please Stand Up‘ featuring Sellers and including an often intimate commentary from Spike Milligan, who also appeared in The Magic Christian. It’s well documented that Sellers was a hugely complex and difficult character and few people really could say they knew him, with the possible exception of Milligan, whose own battles with depression are well documented. In the commentary Milligan talks about Sellers’ loneliness and the word ‘revenge‘ is used regularly. It became clear, according to Milligan, that The Magic Christian was Sellers’ revenge on all the people from the ‘establishment’ to the BBC to film producers, even to women, who all apparently ‘rejected‘ him somehow in the past. In a way, as Guy Grand, he was able to show the human race up as venal, greedy and immoral when offered enough money, similar to the way that Peter Sellers, now at the peak of his fame, was able to make and break careers himself. At one point Sellers is interviewed on the set of The Magic Christian and he admits that, ‘You can buy anyone in the film industry, even myself.’

The film is very sixties in its abandonment of a conventional linear narrative and is made up of a series of vignettes, all based around an elaborate prank or hoax engineered by Guy Grand and his recently adopted son, Youngman, played by Starr. Why Guy Grand suddenly decided to take revenge on all the people he thought ‘had their price‘ is uncertain. Did he wake up suddenly one morning and decide he’d had enough or had these hoaxes been going on for some time. And why did he adopt Ringo Starr? Narrative credibility is certainly not part of this film, which was a very sixties trope.

It’s uncertain what the budget for this film was but given the cast it attracted it must have been pretty generous. With Sellers on board funding was virtually guaranteed and by bringing in Beatle Ringo Starr this will have been the financial icing on the cake, ensuring a young hip audience for what was an extremely hip project. It’s fair to say the film didn’t need so many very well known names in very small parts. Did they really need Dickie Attenborough as the coach of the Oxford boat crew to deliver a couple of lines? Or an uncredited Yul Brynner as a drag artist lip-synching to Noel Coward’s camp classic ‘Mad About The Boy, to a silent Roman Polanski? Probably not, but it all added to the sixties mayhem. Other big, and probably expensive, names included Raquel Welch, Laurence Harvey, Christopher Lee and Wilfred Hyde-White. Given it was Sellers’ pet project it seemed very much a case of him calling in some favours from his Hollywood pals.

Ringo Starr‘s role in the film is an odd one. His presence will certainly have appealed to the money men bankrolling the film. As probably the best actor out of the four Beatles, he had a bit of an acting track record having appeared in Terry Southern’s Candy and been the lead Beatle in Magical Mystery Tour, Help and A Hard Day’s Night. Despite this, the part of Youngman Grand was actually written with John Lennon in mind. Although Starr and Sellers apparently got on well during the filming, Sellers is reported to have been determined that Ringo stole none of his thunder in the film and a number of Ringo’s funnier lines were appropriated by Sellers, leaving Ringo with relatively little to do or say. In fact, Starr’s role is really just as a stooge to listen to Sellers’/ Grand’s philosophising. At this point in Sellers’ career, this was a fairly common occurrence in films he was starring in. Sellers’ meddling even extended to a strange incident involving John Cleese.

A pre-Python John Cleese and Graham Chapman had already written a treatment of the book for screen but on reading it, Seller’s threw out most of it. The only parts of their version that survived in the film were the the Sotheby’s scene where Guy Grand pays a huge amount for a Rembrandt and proceeds to cut out the artist’s nose from the picture in front of an aghast director played by Cleese. The other part of the film that survived was the sequence where Guy Grand bribes the Oxford team competing in that most English of traditions of ‘fair play’, the university boat race. Sellers reportedly tried to have Cleese fired from the film and put pressure on director Joe McGrath to remove him. Why he attempted this is uncertain. Some say it was because Cleese was upstaging Sellers in the scene, something Sellers at this time could not countenance, others claim it was because Sellers felt Cleese was no good in the scene. In his definitive study of Sellers, ‘The Life and Death of Peter Sellers‘, Roger Lewis quotes Sellers as shouting at Cleese ‘Jesus Christ, what are you doing?’ in front of the whole crew. Cleese has talked a number of times about how nervous he got before performing and maybe his nervousness having to perform next to a legend like Sellers took its toll. Either way, the incident was an interesting example of just how difficult Sellers was to work with and Cleese wasn’t fired but it was a scene Sellers was never happy with.

A couple of other interesting Python references to this film. Firstly, Cleese and Chapman originally wrote the famous and very funny ‘Mouse Problem‘ sketch for this film, later used in the first series of Monty Python, which was rejected by Sellers. It’s also possible that a wonderfully sixties strange cartoon sequence near the beginning of the film may have been the first public, though uncredited, example of Terry Gilliam animation.

The film’s late 60s/ early 70s vibe is bolstered also by the use of a few very well known British TV faces such as boxing commentator Harry Carpenter, radio announcer and boat race commentator John Snagge, reporter Alan Whicker and news anchors Michael Aspel and Michael Barrett. With a few very entrenched establishment figures in that line-up, one wonders what they thought they were getting themselves into. Were they given a script to read beforehand and if so did they read it? Was it explained to them what the film was actually about and if so, did it bother them? As Guy Grand regularly explained in the film, ‘Everyone has his price.’ Carpenter’s sequence is especially funny where he is commentating on a boxing match when the protagonists suddenly stop and begin to make love to each other, disgusting the macho viewing audience, baying for blood. I remember during the 70s Carpenter interviewing a very bling Elton John on Sportsnight after his team, Watford, had just beaten the mighty Manchester United. After a smiling Elton had departed Carpenter grinned into the camera and giggled, ‘That result really made his earrings sparkle.’ Harry wasn’t going to let that sort of unmacho display go unchecked! So it’s my firm belief that Harry had no idea what he was really commentating on. Or maybe he did, as Guy maintains everyone has their price…

The film is also populated by well-known British and American acting faces. A few of Sellers’ friends were dragged in (and he didn’t have too many real friends) such as Graham Stark, David Lodge and Spike Milligan. The scene with Spike Milligan as an officious traffic warden is particularly funny. Milligan has just given Guy Grand a parking ticket, not something that would bother the hugely wealthy Grand but he sees a chance to subvert British authority by paying Milligan a ridiculous amount of money to eat the parking ticket, which he, of course, does. As Grand is driving away Milligan shouts ‘And let that be a lesson to you!’ The scene has an improvised feel to it and it’s almost like it’s been crowbarred into the film, which it maybe has. There are a number of scenes which seem improvised and these are often the funniest and most interesting.

Other British acting stalwarts like Hattie Jacques, who plays a horrendous upper class snob called Ginger who talks about enjoying a book on Nazi atrocities. And, her then husband, the excellent John Le Mesurier as an umpire at the boat race. Clive Dunn, Patrick Cargill (one of the stars of ‘Help‘), Dennis Price and Frank Thornton all turn up at various points amongst many other British acting faces. Even Christopher Lee is happy to put in a turn as his most famous character Count Dracula who turns up on the bogus cruiser The Magic Christian to add to the mayhem. I do wonder if any actors turned down a role as they didn’t like the film’s themes? Unlikely, if Guy Grand’s philosophy holds any water. And it would be nice to think that some may even have approved of it.

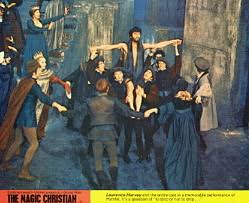

One of the first sequences featured actor Laurence Harvey as Hamlet. Whether this was meant as a bit of a send-up is unknown as Harvey was never considered an actor with a particularly great range. Guy Grand‘s joke here was that Harvey (and he is referred to in the scene as Laurence Harvey) suddenly begins to perform a strip routine during Hamlet’s famous soliloquy. There are a few gasps from the audience, but, true to good old British convention, no one protests, gets up and leaves or causes a fuss at all. Some elderly gentlemen even appear to enjoy it. And this, I believe, is at the bottom of all Guy’s pranks, the fact that people, particularly the upper classes, will huff, puff and often disapprove but no one will do a blind thing about it.

As a post script to this sequence, what for me, was quite a cruel joke seemed to be played out during the credit roll. It was fairly well known in the film business that Harvey was gay but that his public image portrayed him as wildly heterosexual. The credits list him as playing Hamlet right under another film character who was listed as Laurence Faggot. Was this a rather nasty joke played on Harvey by Sellers, who was certainly capable of such cruelty, or maybe by Terry Southern who may not have approved of Harvey remaining steadfastly in the closet? It’s quite possible Harvey was in on it as, according to people who knew him, he was pretty honest about his acting and his public persona, but, either way, it seems something of a coincidence that the other character was not only named ‘Laurence‘ but was also spelled in the same way to Harvey.

Homosexuality is just one of the, for the time, taboo themes explored by the film. During the fateful voyage of The Magic Christian, camp, virtually naked, male dancers provide the floor show. As they thrust their crotches towards a bigoted military type in the audience, once again, no one walks out or even complains. They just look embarrassed and pretend it isn’t happening. The same theme, as mentioned, was explored in the boxing sequence, although the more macho crowd booed its disapproval. But, still, no one tried to stop it…

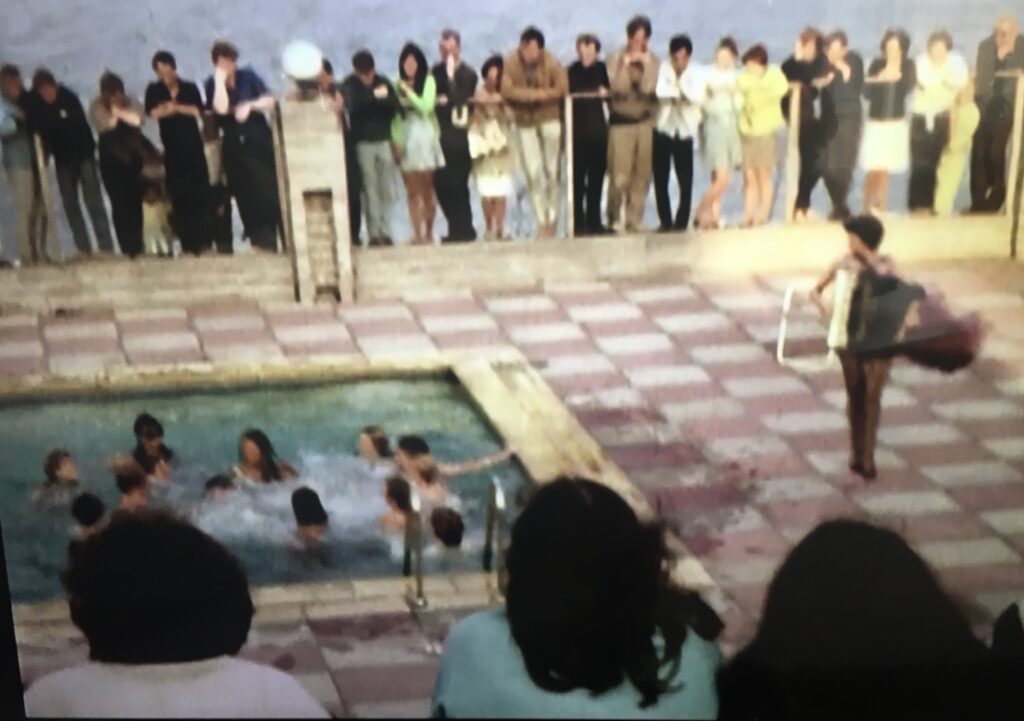

The final scene of bowler-hatted City types diving into the vat of effluent to rescue wads of money Guy Grand had dropped into it was originally supposed to be filmed at the foot of the Statue of Liberty. Bizarrely, the production had been given approval by the New York authorities for this to take place. Clearly they hadn’t read the script (or been given one!) and Sellers, Starr, Joe McGrath et al all sailed to the US on the QE2 to film this scene. When the company financing the film got wind of this (so to speak) they withdrew support and Sellers had to use his not inconsiderable influence to find the money to finish the film. This last scene was eventually shot on the banks of the Thames behind The National Theatre.

A few American stars were prepared to turn up just for a cameo such as Raquel Welch, Yul Brynner and, oddly, Roman Polanski (only a few months before the Manson murders) to no particular narrative point, but they clearly were happy to do Sellers a favour. And one of the weirder appearances included 50s comedy icon Jimmy Clitheroe who turned up during the chaos of the The Magic Christian apparently sinking.

In an odd way the wrangling and the problems that beset The Magic Christian are all part of a wider 60s laissez-faire approach to film making by some artists. Although completely different to what Sellers was used to with Kubrick, for example, it allowed him to influence the film totally to achieve the points he wanted to make. The range of, what Cleese referred to as ‘celebrity walk-ons’, also contributed greatly to the sixties vibe, although, admittedly, only possible in retrospect, and the various contributions of The Beatles cannot be underrated. The left-field sensibility of the text with its images of Che Guevara, Mao Tse Tung and counterculture sloganising root it firmly in the late 60s, only a year after the student protests of 1968 which almost brought down the French government. And ultimately with the confluence of Sellers, Southern, The Beatles, Monty Python and a who’s who of British acting talent, The Magic Christian plants a flag firmly which states ‘This is, and was, the sixties!’

Sadly, films were never quite the same again.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/R-10592291-1501739185-7455.mpo.jpg)